Vision transformer properties

Transformers crossed over from natural language into computer vision in a few low-key steps until the An Image is Worth 16x16 Words paper exploded into the machine learning scene late in 2020.

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) were the dominant architectures in computer vision tasks until transformers arrived on the scene. When I started studying vision transformers, I assumed they were a replacement for CNNs and RNNs. I learned that they are more than that. They are a fundamentally different approach to the problem, resulting in some interesting properties.

In this article we will review transformers’ properties in computer vision tasks that set them apart from CNNs and RNNs.

If you haven’t read the paper yet, start with the accompanying blog post Google AI Blog: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. It has a nice animation and covers the topics in the paper at a higher level. This six-minute video from AI Coffee Break with Letitia is an excellent introduction to the paper or a refresher if it has been a while since you read it.

If this is your first encounter with transformers, start with transformers in natural language processing to learn the fundamental concepts, then come back to vision transformers. Check out Understanding transformers in one morning if you are not yet familiar with the topic.

How transformers process images

First, a brief review of how transformers were adapted from natural language processing (NLP) to computer vision.

Transformers operate on sequences. In NLP the sequence is a piece of text. For example, in the sentence “the cat refused to eat the food because it was cold” we can correlate the word “it” to “food” (not “cat”) and use that to illustrate the concept of “attention.” It is easy to conceive text as a sequence of words and imagine transformer concepts that way.

But what is a “sequence” in computer vision? That is the first significant difference between transformers in computer vision and transformers in NLP.

A naive solution would be to treat an image as a sequence of pixels. The problem with this approach is that it generates humongous sequences. A 256 x 256 RGB image, commonly used to train models, results in a sequence of 196,608 pixels (256 x 256 x 3 RGB channels). This large sequence would require too many computing resources for training and inference. To help visualize: a 400-page book has about 200,000 words. In this one-to-one mapping of pixels to words, it would be the equivalent of feeding that book to a transformer network at once.

To make the problem tractable, An Image is Worth 16x16 Words partitions images into squares called patches. Each patch is the equivalent of a token in an NLP transformer. Back to the 256 x 256 image, partitioning it into 16 x 16 squares results in 256 patches (tokens). Each patch is still a large number of pixels, but the problem is more tractable now because the number of tokens is much smaller.

In addition to the patches, the network has one more token, the class token. This token is the image classification (“cat”, “dog”, …). Beyond that, the transformer network in An Image is Worth 16x16 Words is the same as the transformers used in natural language processing. In the words of the paper, “The “Base” and “Large” models are directly adopted from BERT”.

The picture below, from Google’s blog post, shows the network architecture. Token zero is the class token. The patches are extracted from the image and used as tokens. This transformer is known as ViT, the vision transformer. The term ViT is commonly used in the literature to refer to this architecture.

How are transformers different from CNNs in computer vision?

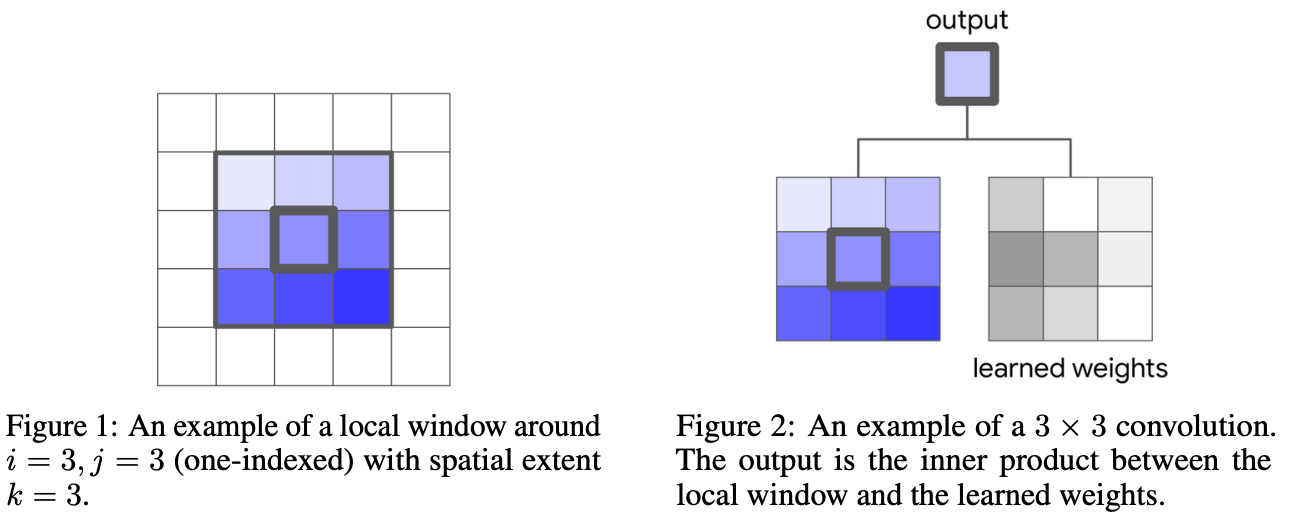

Convolutional neural networks (CNN) work in small image areas. The learned weights are related to that small area, as shown in this picture from Stand-Alone Self-Attention in Vision Models.

In other words, the concept of “locality” (pixels closer to each other are related) is part of the CNN architecture as a prior, or inductive bias, a piece of knowledge that the network creators embedded into the network’s architecture. This piece of knowledge makes assumptions about what the best solution is for a specific problem. Perhaps there are better ways to solve the problem, but we are constraining the solution space to the inductive biases that are part of the network architecture.

On the other hand, a transformer network doesn’t have such inductive biases embedded into its architecture. For example, It has to learn that “locality” is a good thing in computer vision problems on its own.

This lack of inductive bias in the network architecture is a fundamental difference between transformers and CNNs. In more practical terms, a transformer network does not make assumptions about the structure of the problem. As a result of that, the network has to learn the concepts.

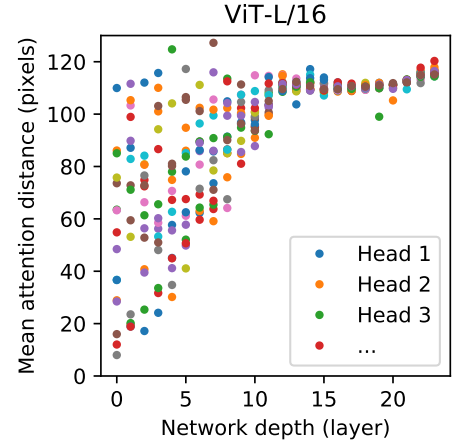

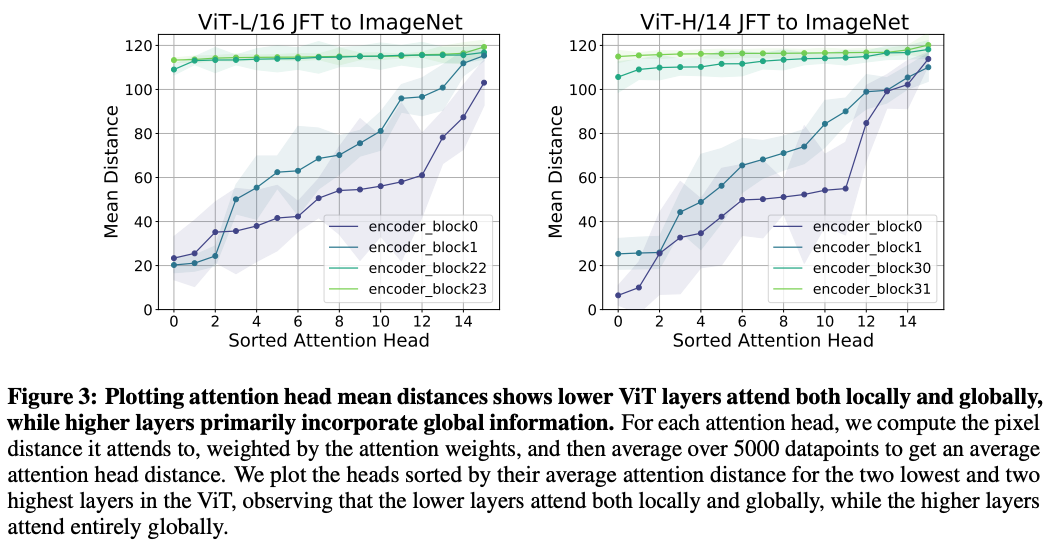

Eventually, the transformer network does learn convolutions and locality. The picture below (from An Image is Worth 16x16 Words) shows the size of the image area attended by each head in each layer. In the lower layers (left), some heads attend to pixels close to each other (bottom of the graph), and other heads attend to pixels further away (top of the graph). As we move up in the layers (right of the graph), heads attend to pixels farther out in the image area (top of the graph). In other words, lower layers have both local and global attention, while higher layers have global attention. The network was not told to behave this way. It learned this attention pattern on its own.

In the words of the authors:

This “attention distance” is analogous to receptive field size in CNNs. We find that some heads attend to most of the image already in the lowest layers, showing that the ability to integrate information globally is indeed used by the model. Other attention heads have consistently small attention distances in the low layers. This highly localized attention is less pronounced in hybrid models that apply a ResNet before the Transformer (Figure 7, right), suggesting that it may serve a similar function as early convolutional layers in CNNs.

Fewer assumptions → more interesting solutions

If, in the end, transformers learn convolutions and locality anyway, what have we gained by using transformers for computer vision? Why go through all the trouble of training transformers to do what CNNs do from the start?

In the words of Lucas Beyer (Standford CS 25 lecture), one of the technical contributors to ViT:

[W]e want the model to have as little of our thinking built-in, because what we may think that is good to solve the task may actually not be the best to solve the task. … [W]e want to encode as little as possible into the model, such that if we just throw massive amounts of data in a difficult task at it, it might think things that are even better than [what we would have assumed]… Ideally, we want [a] model that is powerful enough to learn about this concept [locality] itself, if it’s useful to solve the task. If it’s not useful to solve the task, then if we had put it in, there is no way for the model not to do this.

Lucas Beyer – Standford CS 25 lecture

What else do transformers learn on their own?

So, transformers learned to behave like CNNs. What else could they be learning on their own? By changing how a transformer model is trained, Emerging Properties in Self-Supervised Vision Transformers found out that:

[W]e make the following observations: first, self-supervised ViT features contain explicit information about the semantic segmentation of an image, which does not emerge as clearly with supervised ViTs, nor with convnets. Second, these features are also excellent k-NN classifiers.

Emerging Properties in Self-Supervised Vision Transformers

More concretely, when trained to perform object classification, transformers also learn object segmentation on their own, as shown in the following picture from the paper (for a more lively demonstration, see their blog post).

Segmenting an image requires some understanding of what the objects are, i.e., understanding the semantics of an image and not just treating it as a collection of pixels. The fact that the transformer model is segmenting the image indicates that it is also extracting semantic meanings. From their blog post:

DINO learns a great deal about the visual world. By discovering object parts and shared characteristics across images, the model learns a feature space that exhibits a very interesting structure. If we embed ImageNet classes using the features computed using DINO, we see that they organize in an interpretable way, with similar categories landing near one another. This suggests that the model managed to connect categories based on visual properties, a bit like humans do.

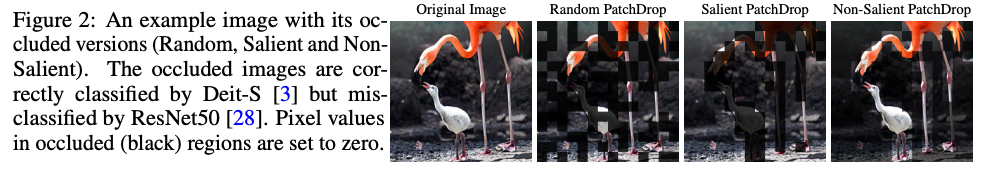

Intriguing Properties of Vision Transformers explores more properties of vision transformers, such as dealing with occlusion better than CNNs.

They introduce a “shape token” to train transformers to be more shape-biased than they naturally are to get automated object segmentation (rightmost column in the picture below).

The [results] show that properly trained ViT models offer shape-bias nearly as high as the human’s ability to recognize shapes. This leads us to question if positional encoding is the key that helps ViTs achieve high performance under severe occlusions (as it can potentially allow later layers to recover the missing information with just a few image patches given their spatial ordering).

Intriguing Properties of Vision Transformers

Vision Transformers are Robust Learners doesn’t have fancy pictures to illustrate what they found, but the results are no less interesting. They found out that without any specific training, vision transformers can cope with image perturbations better than CNNs.

[W]e study the robustness of the Vision Transformer … against common corruptions and perturbations, distribution shifts, and natural adversarial examples. … [W]ith fewer parameters and similar dataset and pre-training combinations, ViT gives a top-1 accuracy of 28.10% on ImageNet-A which is 4.3x higher than a comparable variant of BiT. Our analyses on image masking, Fourier spectrum sensitivity, and spread on discrete cosine energy spectrum reveal intriguing properties of ViT attributing to improved robustness.

Vision Transformers are Robust Learners

Why do vision transformers perform better than CNNs?

We are still in the early stages of understanding the differences between CNNs and vision transformers.

Do Vision Transformers See Like Convolutional Neural Networks? found significant differences in the structure of vision transformers and CNNs.

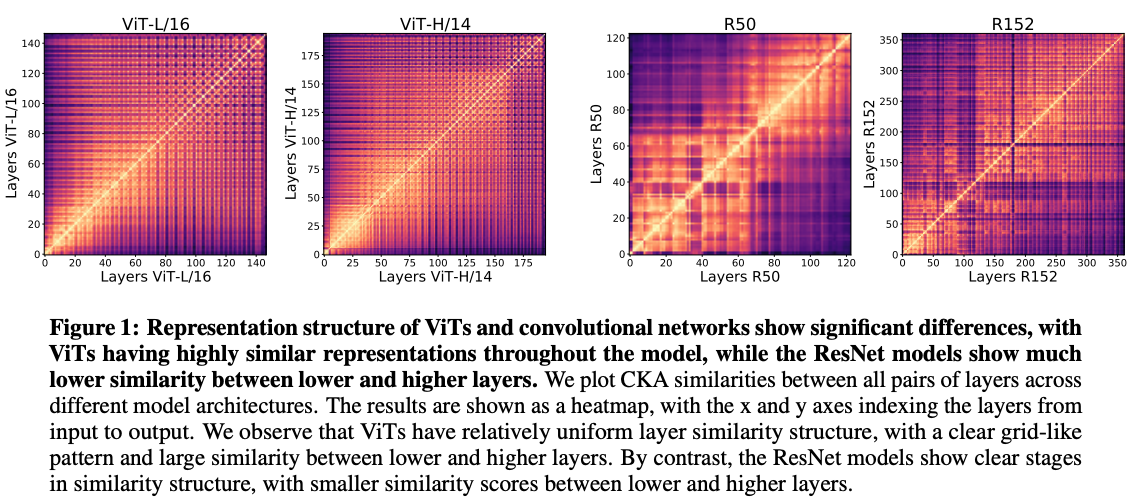

[We use] CKA to study the internal representation structure of each model. … Figure 1 [below] shows the results as a heatmap, for multiple ViTs and ResNets. We observe clear differences between the internal representation structure between the two model architectures: (1) ViTs show a much more uniform similarity structure, with a clear grid like structure (2) lower and higher layers in ViT show much greater similarity than in the ResNet, where similarity is divided into different (lower/higher) stages.

Do Vision Transformers See Like Convolutional Neural Networks?

This is the first significant difference between vision transformers and CNNs.

[T]hese results suggest that (i) ViT lower layers compute representations in a different way to lower layers in the ResNet, (ii) ViT also more strongly propagates representations between lower and higher layers (iii) the highest layers of ViT have quite different representations to ResNet.

Do Vision Transformers See Like Convolutional Neural Networks?

A possible explanation for this structural difference is how the transformer layers learn to aggregate spatial information. CNNs have fixed receptive fields (encoded in the kernel sizes and sequences of layers). Transformers do not have this prior knowledge of “receptive fields” for an image. They have to learn that spatial relations are important in image processing.

The experiments in the paper confirmed the observation in the original ViT paper that transformers eventually settle in a structure where lower layers learn to pay attention locally and globally, while higher layers learn to pay attention globally.

[E]ven in the lowest layers of ViT, self-attention layers have a mix of local heads (small distances) and global heads (large distances). This is in contrast to CNNs, which are hardcoded to attend only locally in the lower layers.

Do Vision Transformers See Like Convolutional Neural Networks?

What was not covered here

Vision transformers are barely a few years old. We are still learning more about how to train them and how they behave. This is a short list of active research areas.

More efficient training and inference

Networks with fewer priors embedded in their design need more data to eventually learn these priors that they don’t have. ViT was trained in a dataset of 300 million images. Large datasets are still private (for the most part) and require a huge amount of computer power to train the model.

New training methods, such as data-efficient image transformers (DeiT) manage to train vision transformers using only ImageNet (while still large, it’s within reach of more research teams and organizations). See Efficient Transformers: a Survey for more work in this area.

Is “attention” needed?

“Attention” is a central concept in transformer networks. But is it really necessary to achieve the same results? Some intriguing research questions if we need attention at all.

- FNet: Mixing Tokens with Fourier Transforms: “We show that Transformer encoder architectures can be sped up, with limited accuracy costs, by replacing the self-attention sublayers with simple linear transformations that “mix” input tokens. … [W]e find that replacing the self-attention sublayer in a Transformer encoder with a standard, unparameterized Fourier Transform achieves 92-97% of the accuracy of BERT counterparts on the GLUE benchmark, but trains 80% faster on GPUs and 70% faster on TPUs at standard 512 input lengths.”

- MLP-Mixer: An all-MLP Architecture for Vision “[W]e show that while convolutions and attention are both sufficient for good performance, neither of them are necessary. We present MLP-Mixer, an architecture based exclusively on multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) … When trained on large datasets, or with modern regularization schemes, MLP-Mixer attains competitive scores on image classification benchmarks, with pre-training and inference cost comparable to state-of-the-art models.”

Catching up with recent developments

Transformers are moving fast. These are some places I use to keep up with recent developments.

- Yanni Kilchner reviews recent papers on his YouTube channel. It is a great place to go after reading a paper to check your understanding and insights you may have missed on a first pass.

- AI Coffe Break with Letitia distills papers into short videos (about ten minutes or so). It’s the ideal format to review the essence of papers.

- For a slower pace but a broader view, the authors of A Survey on Vision Transformer and Transformers in Vision: A Survey publish new versions of their papers every few months.