Would you trust AI to do [X]?

Taking a narrow definition of the question, where [X] is a reasonable application of AI for the current state of the technologies involved, “trust” can be formulated as “it is safe to assume that an AI product can do [X] consistently and that it also detects when it is working outside of its boundaries, reacting accordingly”.

In other words, trust is related to “robustness”, the ability of an AI product to not only do what it is supposed to do, but also to withstand adverse, hostile, conflicting conditions.

The cost of robustness

In software development we use the term “happy path” in the context of programs that do their job well when conditions are perfect but fail miserably if anything is even slightly out of the ordinary. In other words, they work well only when they are on their happy path. The opposite of that is robust programs. They detect that they are off the happy path and take corrective action, even if it is simply refusing to go further to avoid harm.

Writing robust programs is not cheap. I read some time ago that about half of the lines of code in a program are to detect and handle error conditions. I lost the source but can speak from personal experience. In every product I worked on, dealing with what could go wrong and continuing operating, even if in a degraded mode, was at least half of the development time and costs. For mission-critical systems, the ones that need to run 24-7 unassisted, it was more than that. I would guess at least two-thirds of the time and the costs were dedicated to making sure they were robust systems.

Robustness for AI products

AI products are software products. How do we develop robust AI products? We can approach in the same way we do with regular software products, starting from the other end: how can a product fail? Once we understand that, we put countermeasures in place and end up with a robust product.

This goes by the name “failure mode analysis”, “threat modeling”, and similar terms. We are interested in anticipating what could go wrong, then adding code to handle it.

Threat Modeling AI/ML Systems and Dependencies is a comprehensive list of what can go wrong with an AI product (focusing on machine learning). As the name implies, it focuses on malicious attacks. A more practical list is the accompanying list of failure modes in machine learning. Besides malicious attacks, it has a list that they politely call “unintended failures”, also known as “bugs”. Some examples from the “unintended” list:

- Reward hacking: reinforcement learning systems whose reward is not modeled correctly. Some well-known examples include maximizing the score to the detriment of finishing the course (it’s in a game, but picture this reward function in a robot, where “score” is a wrongly-defined measure of success).

- Side effects: reinforcement learning systems that do not have proper constraints in place to achieve their goals. For example: if the goal is “move as fast as possible from point A to B”, a reinforcement-learning robot could knock everything in its way.

- Distributional shifts: the real-life environment does not match what the model was trained on. Sometimes it is simples things. For example, an x-ray imaging system trained on hospital x-ray images may perform significantly worse on images taken with portable x-ray machines (used for emergency cases and in remote clinics).

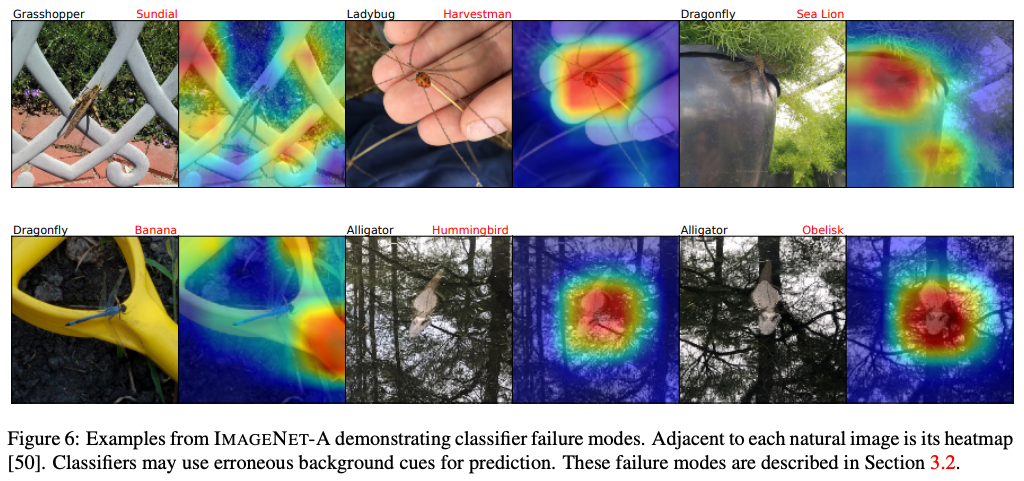

- Natural adversarial examples: the model is confused by naturally occurring examples. It’s sadly fairly simple to confuse classifiers. See the example picture below (source).

- Common corruption: changes to the input, such as zooming, cropping, or tilting images, confuse the system.

- Incomplete testing in realistic conditions: a polite way to say “the developers failed to account for how the world works”.

Side note: research vs. production

Most research papers that publish the results of a model do not cover failure modes. These papers are great research work, but from the research paper to a product, we still need to go through “how to make it robust” work, which will cost the same amount of time and money spent to develop the model described in the paper (or more), based on the discussion of the cost of robustness above.

Even peer-reviewed papers do not perform well, as this review of papers documented:

“Only 10 records were found for deep learning randomised clinical trials, two of which have been published (with low risk of bias, except for lack of blinding, and high adherence to reporting standards) and eight are ongoing. Of 81 non-randomised clinical trials identified, only nine were prospective and just six were tested in a real world clinical setting.”

M. Nagendran et al. — Artificial intelligence versus clinicians: systematic review of design, reporting standards, and claims of deep learning studies

Google’s “production readiness” rubric gives an idea of what it takes to take a machine learning model into production. It’s much more than training a model.

Would I trust AI to do [X]?

Given an AI product that is being used in its well-defined application, I would trust it if I could trust that the organization behind it is aware of robustness practices.

These products come from paranoid organizations, the ones that assume every possible thing that could go wrong will most definitely go wrong sooner or later. They then proceed to protect their products against this hostile world. Those products I trust. Creating such products takes time and lots of money.

Looking from another side, I distrust any product that makes large claims in their first version without backing it up with extended research and trial periods.

Other sources for AI failures

A list of some papers and articles I came across on the topic of “AI failure”.

What to Do When AI Fails – O’Reilly

“What is an incident when it comes to an AI system? When does AI create liability that organizations need to respond to? This article answers these questions, based on our combined experience as both a lawyer and a data scientist responding to cybersecurity incidents, crafting legal frameworks to manage the risks of AI, and building sophisticated interpretable models to mitigate risk.”

Does Object Recognition Work for Everyone?

“The paper analyzes the accuracy of publicly available object-recognition systems on a geographically diverse dataset. This dataset contains household items and was designed to have a more representative geographical coverage than commonly used image datasets in object recognition. We find that the systems perform relatively poorly on household items that commonly occur in countries with a low household income”

The “inconvenient truth” about AI in healthcare

“However, “the inconvenient truth” is that at present the algorithms that feature prominently in research literature are in fact not, for the most part, executable at the frontlines of clinical practice. This is for two reasons: first, these AI innovations by themselves do not re-engineer the incentives that support existing ways of working… Second, most healthcare organizations lack the data infrastructure required to collect the data needed to optimally train algorithms to (a) “fit” the local population and/or the local practice patterns, a requirement prior to deployment that is rarely highlighted by current AI publications, and (b) interrogate them for bias to guarantee that the algorithms perform consistently across patient cohorts, especially those who may not have been adequately represented in the training cohort.”

Secure and Robust Machine Learning for Healthcare: A Survey

“Notwithstanding the impressive performance of ML/DL, there are still lingering doubts regarding the robustness of ML/DL in healthcare settings (which is traditionally considered quite challenging due to the myriad security and privacy issues involved), especially in light of recent results that have shown that ML/DL are vulnerable to adversarial attacks. In this paper, we present an overview of various application areas in healthcare that leverage such techniques from security and privacy point of view and present associated challenges.”

Concrete Problems in AI Safety

“In this paper we discuss one such potential impact: the problem of accidents in machine learning systems, defined as unintended and harmful behavior that may emerge from poor design of real-world AI systems. We present a list of five practical research problems related to accident risk, categorized according to whether the problem originates from having the wrong objective function (“avoiding side effects” and “avoiding reward hacking”), an objective function that is too expensive to evaluate frequently (“scalable supervision”), or undesirable behavior during the learning process (“safe exploration” and “distributional shift”).”