Machine learning, but not understanding

In the expression machine learning, are the machines actually learning anything?

In the book “Artificial Intelligence, a guide for thinking humans” Melanie Mitchell explains that

“Learning in neural networks simply consists in gradually modifying the weights on connections so that each output’s error gets as close to 0 as possible on all training examples.”

Melanie Mitchell — Artificial Intelligence, a guide for thinking humans

Let’s explore what “learning” means for machine learning, guided by Mitchell’s book. More specifically, we will concentrate on “deep learning”, a branch of machine learning that has powered most of the recent advances in artificial intelligence.

All quoted text in this article is from Dr. Mitchell’s book “Artificial Intelligence, a guide for thinking humans”.

An extremely short explanation of deep learning

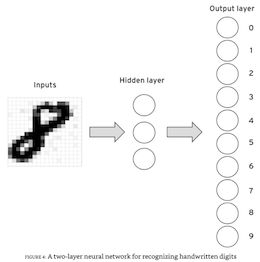

Deep learning uses layers of “units”’ (also called neurons, but some people, including Mitchell and I, prefer the more generic units term, to not confuse with biological neurons) to extract patterns from labeled data. The internal layers are called “hidden layers”. The last layer is called the “output layer”, or the classification layer.

In the following figure (from Mitchell’s book), a neural network comprised of several hidden layers (only one shown) was trained to classify handwritten digits. The output layer has ten units, one for each possible digit.

How does a neural network learn? Back to Mitchell’s quote:

“Learning in neural networks simply consists in gradually modifying the weights on connections so that each output’s error gets as close to 0 as possible on all training examples.”

Going through the sentence pieces:

- training examples: The labeled examples we present to the network to train it. For example, we present a picture of a square or a triangle and its corresponding label, “square” or “triangle”.

- output’s error: How far the network’s prediction is from the correct label of the example picture.

- weights on connections: A large-precision decimal number that adjusts the output of a unit in one layer to the input of a unit in the next layer. The weights are where the “knowledge” of the neural network is encoded.

- gradually modifying: This is the neural network learning process. An algorithm carefully modifies the weights on the connections to get closer to the expected output. Repeating the adjustment step over time (many, many times) allows the network to learn from the training examples.

An important consequence of this process

“The machine learns what it observes in the data rather than what you (the human) might observe. If there are statistical associations in the training data, even if irrelevant to the task at hand, the machine will happily learn those instead of what you wanted it to learn.”

Thus, neural networks are not “learning” in the sense that we would understand the term. They are not learning higher-level concepts from the samples used to train them. They are extracting patterns from the data presented to them during training (and they assume that the labels are correct). That’s all.

Or, as Mitchell puts more eloquently:

“The phrase “barrier of meaning” perfectly captures an idea that has permeated this book: humans, in some deep and essential way, understand the situations they encounter, whereas no AI system yet possesses such understanding. While state-of-the-art AI systems have nearly equaled (and in some cases surpassed) humans on certain narrowly defined tasks, these systems all lack a grasp of the rich meanings humans bring to bear in perception, language, and reasoning. This lack of understanding is clearly revealed by the un-humanlike errors these systems can make; by their difficulties with abstracting and transferring what they have learned; by their lack of commonsense knowledge; … The barrier of meaning between AI and human-level intelligence still stands today.”

Should we be concerned that deep learning is not “learning”? We should, if we don’t understand what it implies for real-life applications.

In the next sections we will explore how neural networks lack the grasp of “rich meanings we humans bring to bear in perception”, illustrating it with some “un-humanlike errors these systems can make; by their difficulties with abstracting and transferring what they have learned; by their lack of commonsense knowledge”.

You can run the examples used in the text with the Jupyter notebook on this GitHub repository. The examples use small pictures to run quickly on any computer.

Telling squares and triangles apart

We will see how a neural network trained to tell squares and triangles apart behaves.

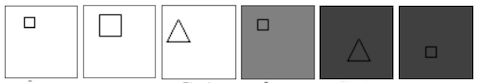

For human beings, the pictures below show squares and triangles. Some are small, some are large, some are in a light background, some are in a darker background. But they are all clearly either a square or a triangle in a frame.

In this section we will go through the typical process of training a neural network to classify squares and triangles:

- Get a dataset with labeled pictures of squares and triangles

- Split the dataset into a training set and a test set

- Train the network with the training set

- Validate the neural network accuracy with the test set

After we are done with that, we will predict similar images to see how the network handles them.

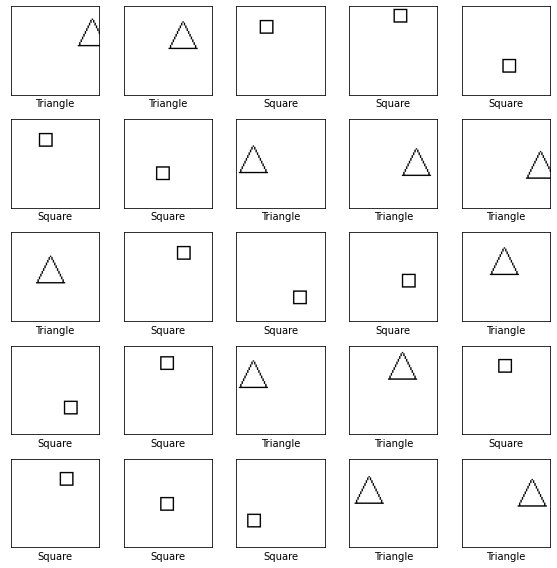

The “squares vs. triangles” training examples

This is how some of the training images look like. Each picture is a square or a triangle in different positions. The dataset has hundreds of these pictures.

The “squares vs. triangles” neural network

We train a convolutional neural network (CNN) to classify a picture as a “square” or as a “triangle”, using the training examples. We chose a CNN architecture because it is well suited to image classification.

If you would like to see the details of the training process, see the Jupyter notebook on this GitHub repository.

How does the neural network perform?

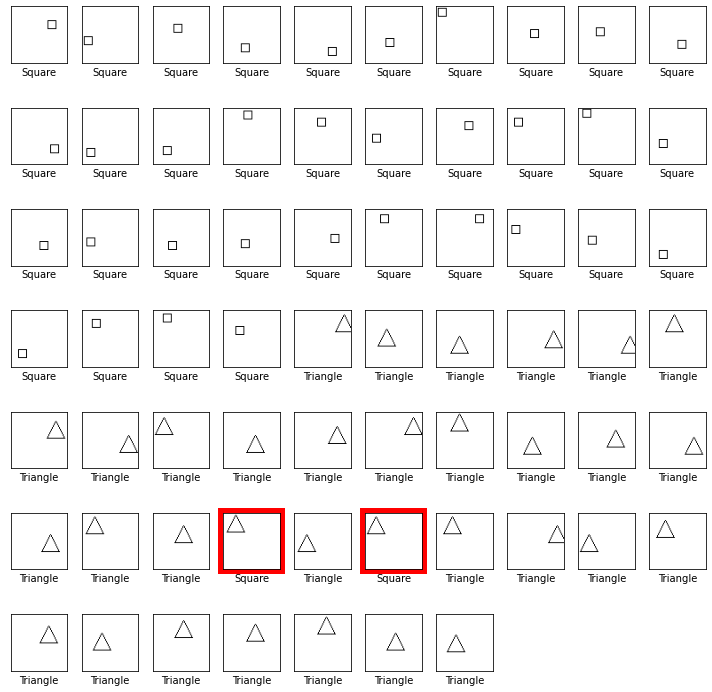

Before we started the training process, we set aside 10% of the pictures to use later (67 pictures). They are pictures that the neural network was not trained on. This is the test set. We use the test set to measure the performance of the neural network.

A traditional measure of performance is “accuracy”. It measures the percentage of pictures in the test set that were correctly classified.

First, we ask the neural network to predict what the pictures are (more details on how that happens here), then we compare with the actual labels and calculate the accuracy.

Our neural network classified 65 out 67 pictures correctly, for an accuracy of 97%. This is a pretty good accuracy for a relatively small neural network that can be trained quickly.

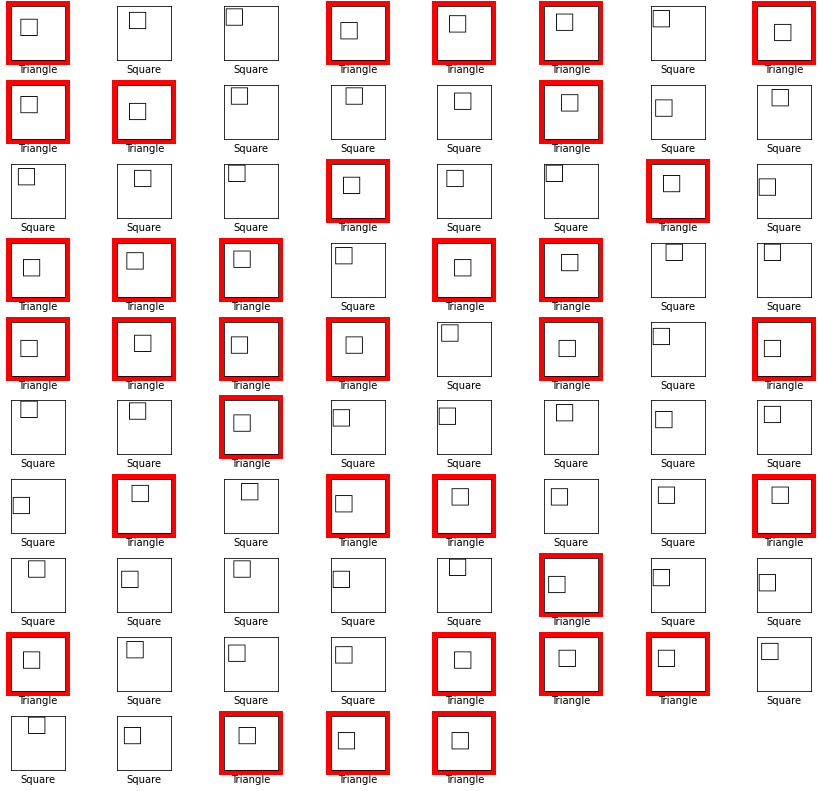

Let’s visualize where the neural network made the mistakes. The picture below shows the mistakes with a red border. All other pictures were classified correctly. Below each picture is the neural network’s classification.

Despite the good accuracy, does the neural network understand the concept of what it is learning?

When are squares not squares?

When they are larger. At least for this neural network.

In this section we will use the neural network we just trained to classify a set of squares. But there is a twist to these squares: they are larger than the ones we used in the training set.

This is how they look like.

Using the neural network, we classify the large squares and calculate the accuracy, just like we did with the test set.

But this time, out of 77 large squares, only 43 are classified as squares. The other 34 are classified as triangles. With an accuracy of 55.8%, the neural network is barely better than flipping a coin.

Below are all the squares in this set and how the neural network classified them. The ones with the red border were incorrectly classified as triangles (there are many of them).

Why does this experiment matter?

The simplest and fastest way to improve this neural network is to increase the size of the training and test sets. In this case, we should add larger squares to the training set and retrain the neural network. It will very likely perform better.

But this does not address the fundamental problem: the neural network does not understand the concept of “square”.

Quoting Mitchell again (emphasis added):

“The phrase “barrier of meaning” perfectly captures an idea that has permeated this book: humans, in some deep and essential way, understand the situations they encounter, whereas no AI system yet possesses such understanding. While state-of-the-art AI systems have nearly equaled (and in some cases surpassed) humans on certain narrowly defined tasks, these systems all lack a grasp of the rich meanings humans bring to bear in perception, language, and reasoning. This lack of understanding is clearly revealed by the un-humanlike errors these systems can make; by their difficulties with abstracting and transferring what they have learned; by their lack of commonsense knowledge; … The barrier of meaning between AI and human-level intelligence still stands today.”

Even if we collect lots and lots and lots of examples, we are confronted with the long-tail problem:

“[T]he vast range of possible unexpected situations an AI system could be faced with.”

For example, let’s say we trained our autonomous driving system to recognize a school zone by the warning sign painted on the road (source):

Then, one day our autonomous driving system comes across these real-life examples (source 1, source 2):

Any (well, most) human beings would still identify them as warning signs for school zones (presumably, the human would chuckle, then - hopefully - slow down).

Would the autonomous driving system identify them correctly? The honest answer is “we don’t know”. It depends on how it was trained. Was it given these examples in the training set? In enough quantities to identify the pattern? Did the test set have examples? Were they classified correctly?

But no matter how comprehensive we make the training and test sets and how methodically we inspect the classification results, we are faced with the fundamental problem: the neural network does not understand the concept of “school zone warning”.

The autonomous driving system lacks common sense.

“…humans also have a fundamental competence lacking in all current AI systems: common sense. We have vast background knowledge of the world, both its physical and its social aspects.”

The neural network may be learning, but it is definitely not understanding.

Not understanding “squares” - part 2

In the first section we changed the shape of an object. In this section we will not change the object. We will change the environment instead.

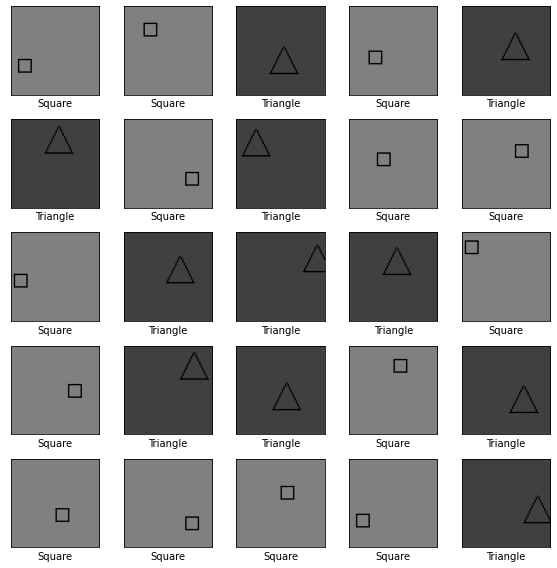

We will train a neural network to classify squares and triangles again. This time they are in different environments, represented by different background colors. The squares are in a lighter background and the triangles are on a dark(er) background (we can think of the backgrounds as “twilight” and “night”).

The picture below shows how they look like.

Following the same steps we used in the first section, we train a neural network to classify the squares and triangles.

Once the network is trained, we use the test set to calculate the neural network accuracy and find out that it is a perfect 100% accuracy score. All squares and triangles in the test set were classified correctly.

If you would like to see the details of the training process, see the Jupyter notebook on this GitHub repository.

So far, so good, but…

In the dark, all squares are triangles

What happens if the squares are now in the same environment as the triangles (all squares are in the “night” environment)?

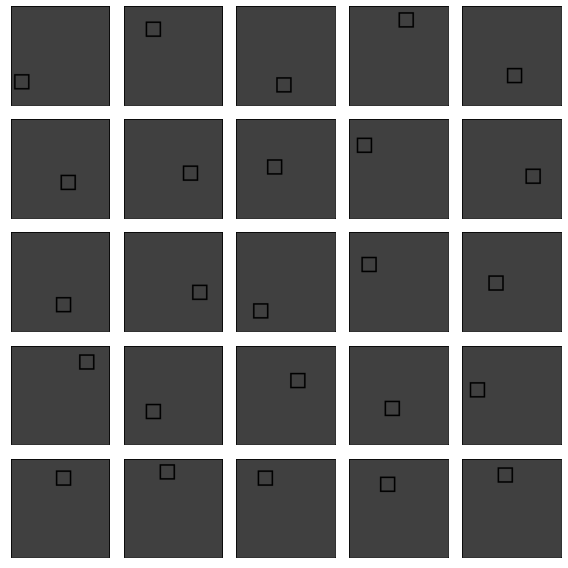

This is how the squares look like in the darker environment.

When we ask the neural network to classify these squares, we find out that the performance is now abysmal. The accuracy is 0%. All squares are misclassified as triangles.

To confirm, we can visualize the predictions. The wrong predictions have a red frame around them (all of them are wrong in this case).

Why does this experiment matter?

The neural network we just trained fails in the same way the first neural network failed: it doesn’t understand the concepts of “square” and “triangle”. It is just looking for any sort of pattern in the training data. It doesn’t know if a pattern makes sense or not, it just knows there is a pattern there.

In this case, the neural network is very likely learning not from the shape, but from the background (a case of spurious correlation). It is assuming that a darker background means “triangle” because it doesn’t really understand the concept of what makes a triangle a triangle.

Sometimes this leads to some funny examples, like the neural network that “learned” to classify land vs. water birds based on the background. The duck on the right was misclassified as a land bird, simply because it was not in its usual water environment (source).

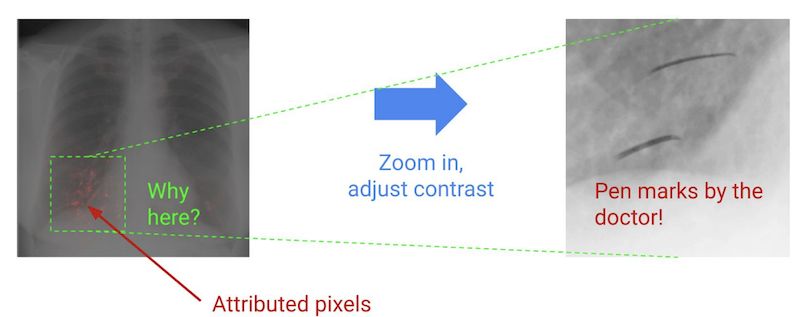

Other times the mistakes are more consequential, for example, when neural networks misclassify X-rays based on markings left by radiologists in the images. Instead of learning actual attributes of a disease, the neural network “learned” from the marks left behind in the images. Images without such marks may be classified as “healthy”. The consequences can be catastrophic (source).

Should we be concerned that deep “learning” is not “understanding”?

Mitchell asks the following question in her book:

“but the question remains: Will the fact that these systems lack humanlike understanding inevitably render them fragile, unreliable, and vulnerable to attacks? And how should this factor into our decisions about applying AI systems in the real world?”

Until we achieve humanlike understanding, we should be concerned that neural networks do not generalize well.

Does it mean we need to stop using neural networks until then? No.

“I think the most worrisome aspect of AI systems in the short term is that we will give them too much autonomy without being fully aware of their limitations and vulnerabilities.”

Deep learning has successfully improved our lives. It’s “just” a matter of understanding its limitations, applying it judiciously, for the tasks that it’s well suited.

To do that we need to educate the general public and, more importantly, the technical community. Too often we hype the next “AI has achieved humanlike performance in [some task here]”, when in fact we should say “under these specific circumstances, for this specific application, AI has performed well”.

Source code for the experiments

The source code for the experiments described here is on this GitHub repository. It uses small pictures to run quickly on a regular computer.

Feel free to modify the pictures, the neural network model, and other parameters that affect the results.

But remember that when the results improve, it’s not the neural network that is learning more all of a sudden. You are improving it.

“Because of the open-ended nature of designing these networks, in general it is not possible to automatically set all the parameters and designs, even with automated search. Often it takes a kind of cabalistic knowledge that students of machine learning gain both from their apprenticeships with experts and from hard-won experience.”

Melanie Mitchell — Artificial Intelligence, a guide for thinking humans