Applications of transformers in computer vision

This article describes the evolution of transformers, their application in natural language processing (NLP), their surprising effectiveness in computer vision, ending with applications in healthcare.

It starts with the motivation and origins of transformers, from the initial attempts to apply a specialized neural network architecture (recurrent neural network – RNN) to natural language processing (NLP), the evolution of such architectures (long short-term memory and the concept of attention), to the creation of transformers and what makes them perform well in NLP. Then it describes how transformers are applied to computer vision. The last section describes some of the applications of transformers in healthcare (an area of interest for my research).

Side note: It was originally written as a survey paper for a class I took. Hence the references are in bibliography format instead of embedded links.

if you are new to transformers, see Understanding transformers in one morning and Vision transformer properties.

The origins of transformers – natural language processing

When context matters

In some machine learning applications, we train models by feeding one input at a time. The trained model is then used in the same way: given one input, make a prediction. The typical example is image recognition and classification. We train the model by feeding one image at a time. Once trained, we feed one image and the model returns a prediction.

However, there are other classes of problems where a single input is not enough to make a prediction. Natural language processing is a prominent example. When translating a sentence, it is not enough to look at one word at a time. The context in which a word is used matters. For example, the Portuguese word legal is translated in different ways to English.

Isso é um argumento legal → This is a legal argument

Isso é um seriado legal → This is a nice TV series

In these applications of machine learning, context matters. The translation of “legal” depends on the word that came before it. If we represent the phrases as vectors (so a model can process them), we could, for example, represent the first phrase as the vector p1=[87,12,43,215,102] and the second sentence as the vector p2=[87,12,43,175,102].

A model attempting to translate the word “legal”, encoded as 102, must remember what came before it. The model must translate 102 one way if it was preceded by 215 (p1) and another way if it was preceded by 175 (p2).

The model must have a “memory” of what it has seen so far. Or, in other words, the model’s output is contextual: it is based not only on its current state (the current input – the current word) but also on previous states (what came before the current input – the words that came before). To understand the context, the model must “remember” what it has seen so far, instead of taking only one input at a time, i.e. the model must work with a sequence of input values.

Remembering the past – recurrent neural networks

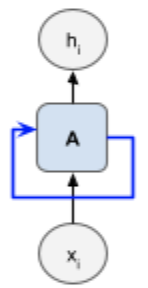

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) are a class of networks that can model such problems. The figure below shows the standard representation of an RNN cell. The blue arrow indicates the “temporal loop” in the network: the result from a previous input, known as the state, is fed into the network when processing a new input. Using the state from a previous input when processing new input allows the network to “remember” what it has seen so far.

The temporal loop can be conceptually represented as passing the state from the past steps into the future steps. In the figure below, the RNN cell is unrolled (repeated) to represent the state from previous steps passed into the subsequent ones (this process is also called “unfolding” the network).

Forgetting the past – vanishing and exploding gradients

RNNs are trained with a variation of back-propagation, similar to how we train other types of neural networks. First, we choose how many steps we will unroll the network, and then we apply a specialized version of back-propagation (Ian et al., 2016).

Ideally, we would like to create an RNN with as many unrolled steps as possible, to have as much context as possible (i.e. remember very large sentences or even entire pieces of text). However, a large number of unrolled steps has an unfortunate effect: vanishing and exploding gradients, which limits the size of the network we can build (Bengio et al., 1994) (Pascanu et al., 2013).

In practice, the result is that we have to limit the number of unrolled steps of an RNN, thus limiting how far back the network can “remember” information.

Going further into the past – long short-term memory

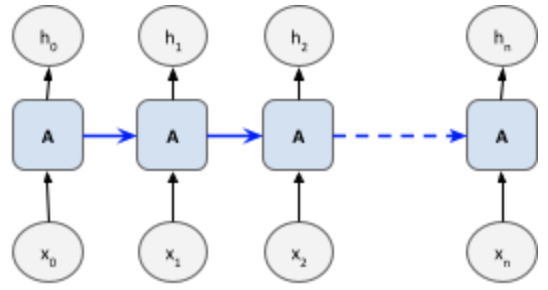

Long short-term memory (LSTM) is a recurrent network architecture created to deal with the vanishing and exploding gradient problem of the classical RNN architecture (Hochreiter & Schmidhuber, 1997). They do so by having a more complex cell design. In this design, the gradients are all contained within the LSTM cell, making them more stable because they no longer have to traverse the entire network.

The figure below, from (Greff et al., 2017), compares an RNN cell (left) with a typical LSTM cell (right), including the “forget gate” that enables it to learn long sequences that are not partitioned into subsequences (Gers et al., 1999).

Deciding where to look – attention

With LSTM we have a solution to look further into the past and process larger sentences. Now we need to decide where to look when processing a sentence because the order of the words is important for language processing. A model cannot mindlessly translate one word at a time.

A typical example where the order of words matters is the placement of adjectives. Back to the first example, we can see that the placement of “legal” varies in each language.

Isso é um argumento legal → This is a legal argument

How does a model know that “legal” goes to a different position in the translated phrase? The solution has two parts. First, the model needs to process the entire sentence, not each word separately. Then, the model needs to learn that it has to pay more attention to some parts of the phrases than others, at different times (in the example above, although “legal” comes last in the input, the model has to learn that in the output it must come first).

RNN encoder/decoder networks (Cho et al., 2014) are used for the first part, processing the entire sentence. An encoder/decoder has two neural networks: one that converts (encodes) a sequence of words into a representation suitable to train a network, and another network that takes the encoded representation and translates (decodes) it. The decoder, armed with a full sequence of words and not just one word, implements the second part of the solution: decide in which sequence it must process the words (which may not be in the same order they were received, as in this case).

This process is known as attention (Bahdanau et al., 2014) (Luong et al., 2015), as in “where should the decoder look to produce the next output”.

“Attention is all we need” – transformers

Adding the concept of attention significantly improved the accuracy of the networks, but it is still part of a time-consuming process, the training of the encoder and decoder RNNs.

If what we want is the information to calculate attention, can we do that in a faster way? It turns out we can. Transformer networks dispense with RNNs and directly compute the important piece of information we want, attention. They achieve better accuracy for a fraction of the training time (Jakob, 2017) (Vaswani et al., 2017).

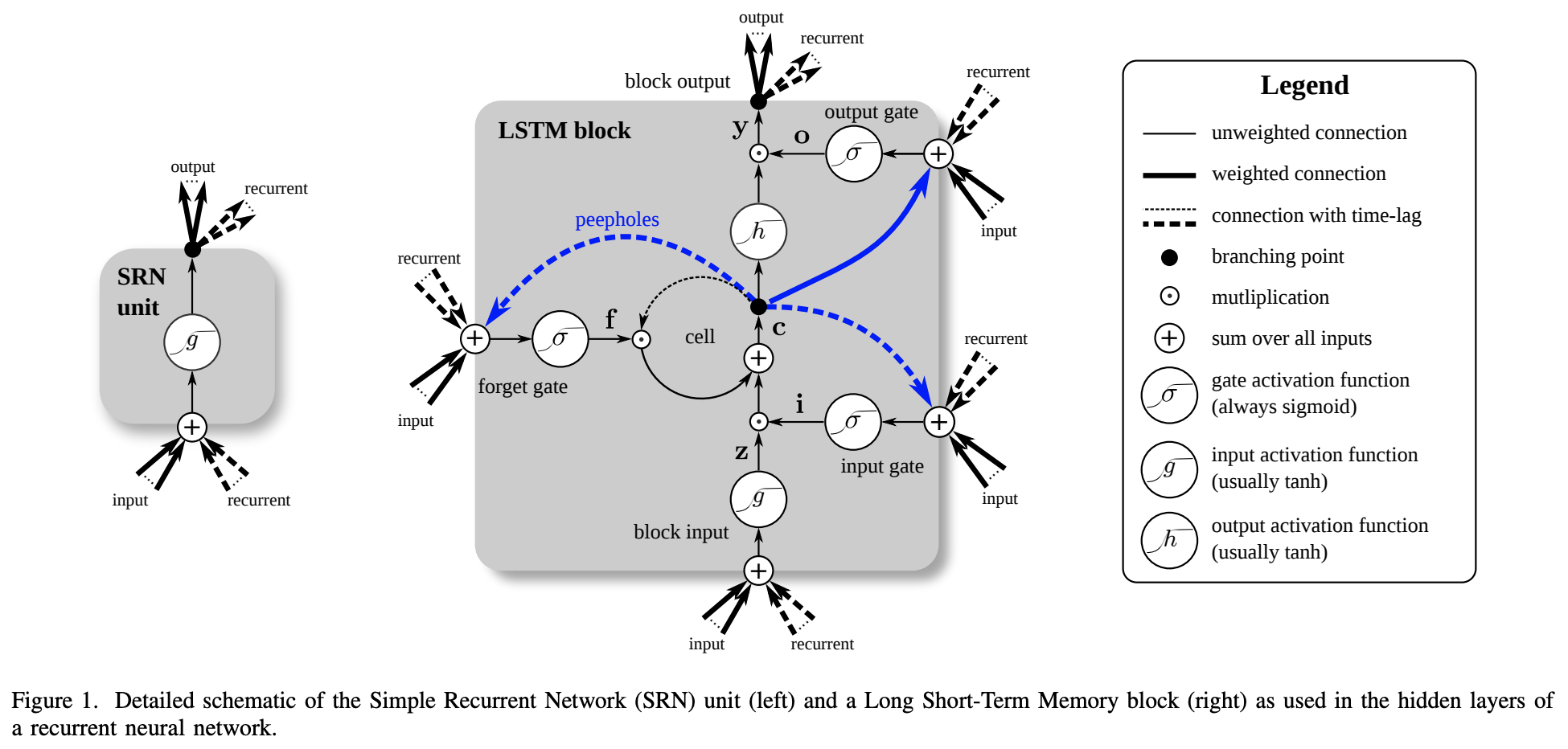

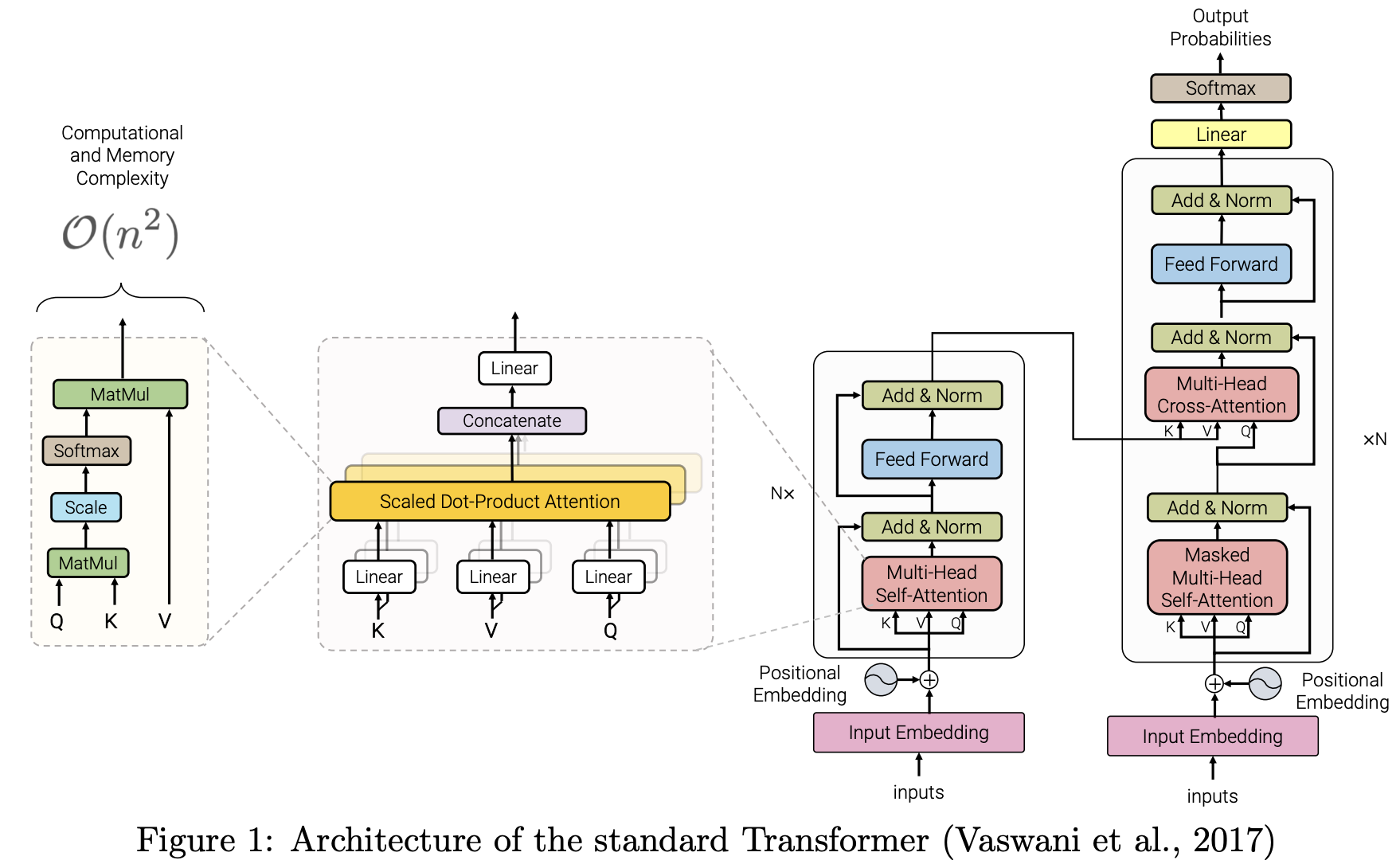

Instead of using RNNs, transformers use stacks of feed-forward layers (a simple layer of neurons, without cycles, unlike RNNs). The figure below, from the original paper (Vaswani et al., 2017), shows the network architecture.

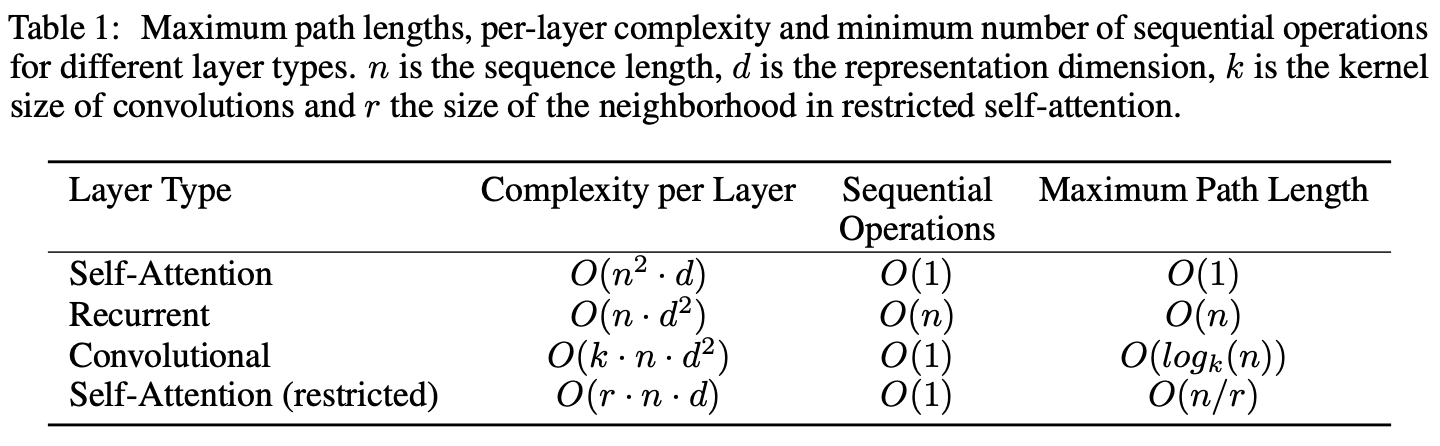

Dispensing with RNNs has two effects: the training process can be parallelized (RNNs are sequential by definition: the state of a previous step is fed into the next step) and computations are much faster. The following table, from (Vaswani et al., 2017), shows the smaller computational complexity of the transformer model compared to RNNs and convolutional neural networks (CNNs).

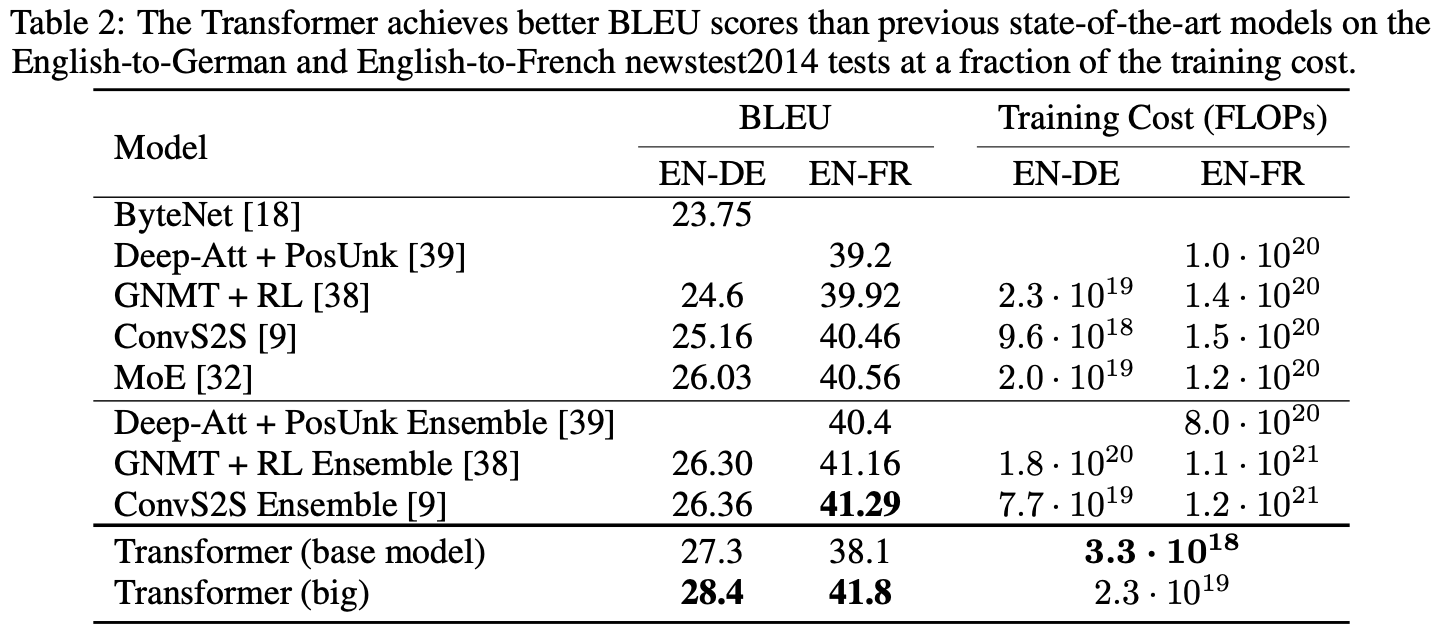

The rightmost columns of the following table, also from (Vaswani et al., 2017), compares the training cost (in FLOPs). The transformer models are two to three orders the magnitude less expensive to train.

The best performing language models today, BERT (Devlin et al., 2019), GPT-2 (Radford et al., 2019), and GPT-3 (Brown et al., 2020), are based on the transformer architecture. The combination of a simpler network and parallelization allowed the creation of these large, sophisticated models.

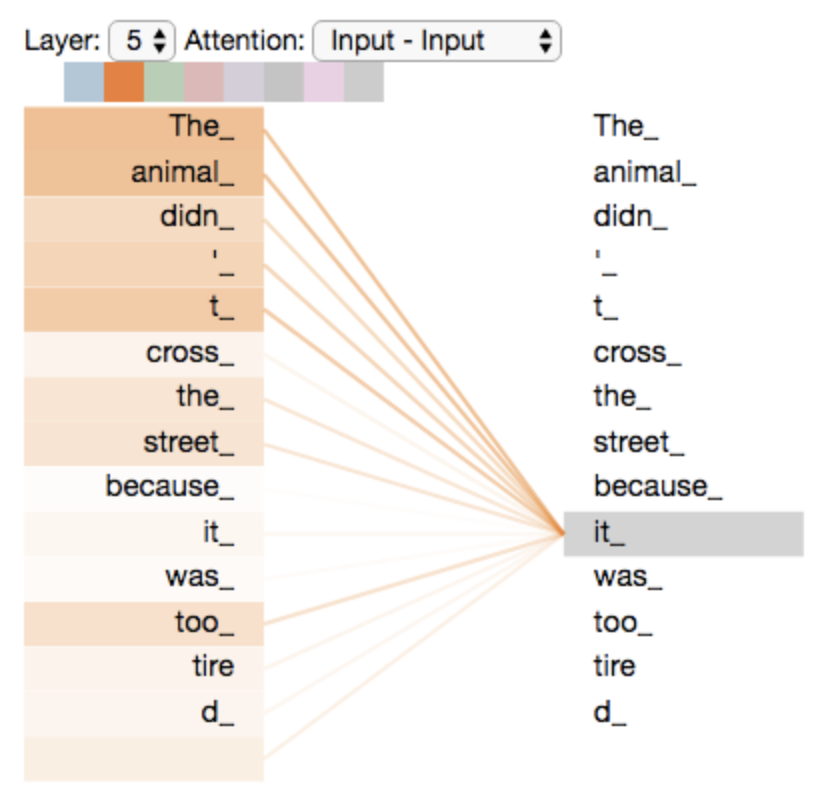

A key concept of the transformer architecture is the “multi-head self-attention” layer. “Multi” refers to the fact that instead of having one attention layer, transformers have multiple attention layers running in parallel. In addition, the layers employ self-attention (Cheng et al., 2016) (Lin et al., 2017). With such a construct, transformers can efficiently weigh in the contribution of multiple parts of a sentence simultaneously. Each self-attention layer can encode longer range dependencies, capturing the relationship between words that are further apart (compared to RNNs and CNNs).

The ability to pay attention to multiple parts of the input and the encoding of longer-range dependencies results in better accuracy. The figure below (Alammar, 2018b) shows how self-attention allows a model to learn that “it” refers more strongly to “The animal” in the sentence.

Research continues to create larger transformer models. A recent advancement in the architecture of transformers is Big Bird (Zaheer et al., 2021). It removes the original model’s quadratic computational and memory dependency on the sequence length by introducing sparse attention. By removing the quadratic dependency, larger models can be built, capable of processing larger sequences.

Transformers in computer vision

The concepts of “sequence” and “attention” can also be applied to computer vision. The original applications of attention in image processing used RNNs, like the NLP counterparts. Neural networks with attention were used for image classification (Mnih et al., 2014), multiple object recognition (Ba et al., 2015), and image caption generation (Xu et al., 2016). These applications of attention to computer vision experienced the same issues that afflicted NLP architectures based on RNN: vanishing or exploding gradients and long times to train the model.

And, just like in NLP, the solution was to apply self-attention, using the transformer architecture. One of the first applications of transformers in computer vision was in image generation (Parmar et al., 2018). (Carion et al., 2020) applied transformers to object detection and segmentation using a hybrid architecture, with a CNN used to extract image features.

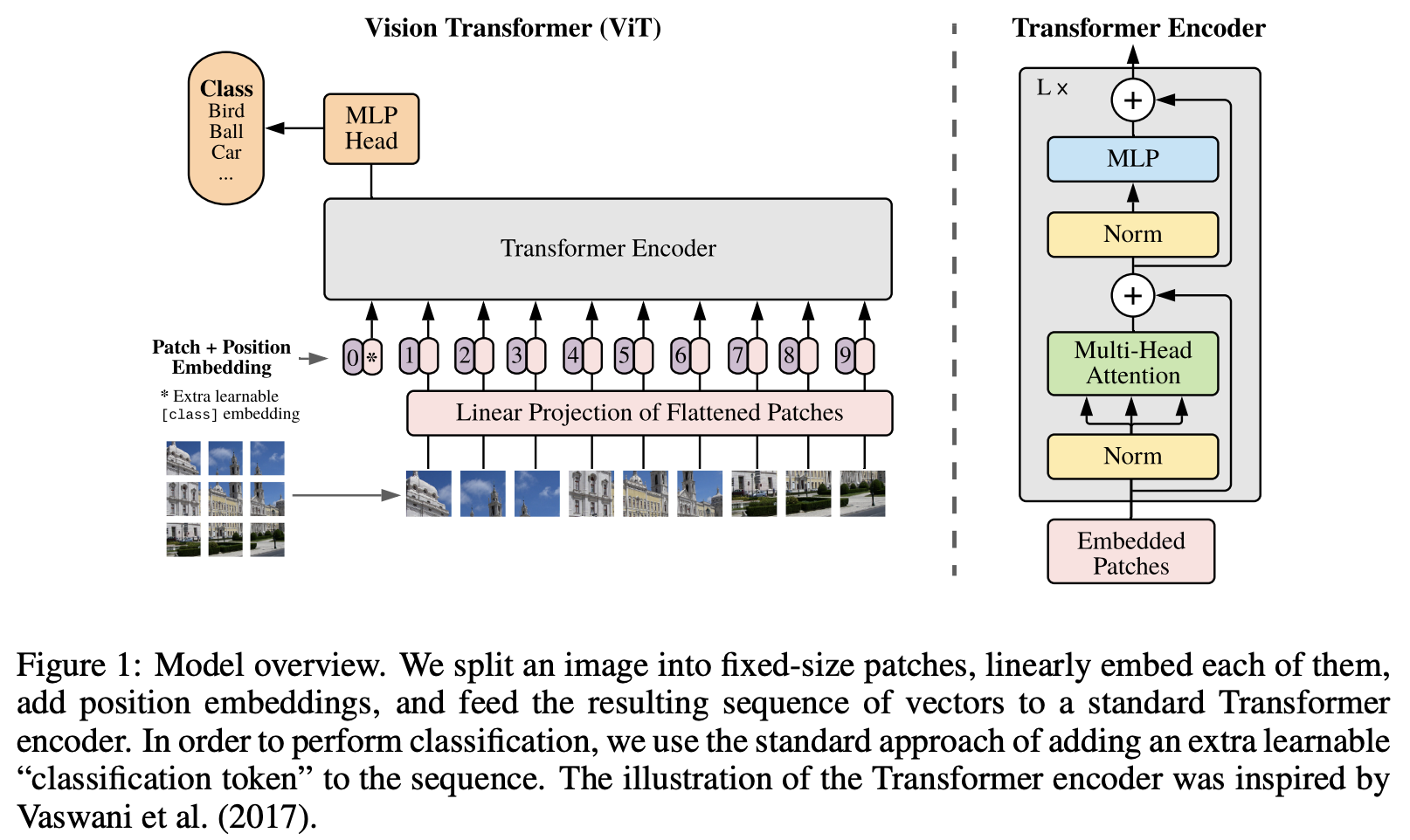

Then (Dosovitskiy et al., 2020, which includes references to earlier works they built upon), dropped all other types of networks, creating a “pure” transformer architecture for image recognition. In the figure below, from that paper, we can see the same elements of the NLP transformer architecture, now applied to computer vision: the lack of more complex networks (like RNN or CNN) that results in fast training time, the concept of sequences (created by splitting the image into patches), and the multi-headed attention. This architecture is known as ViT (Vision Transformer).

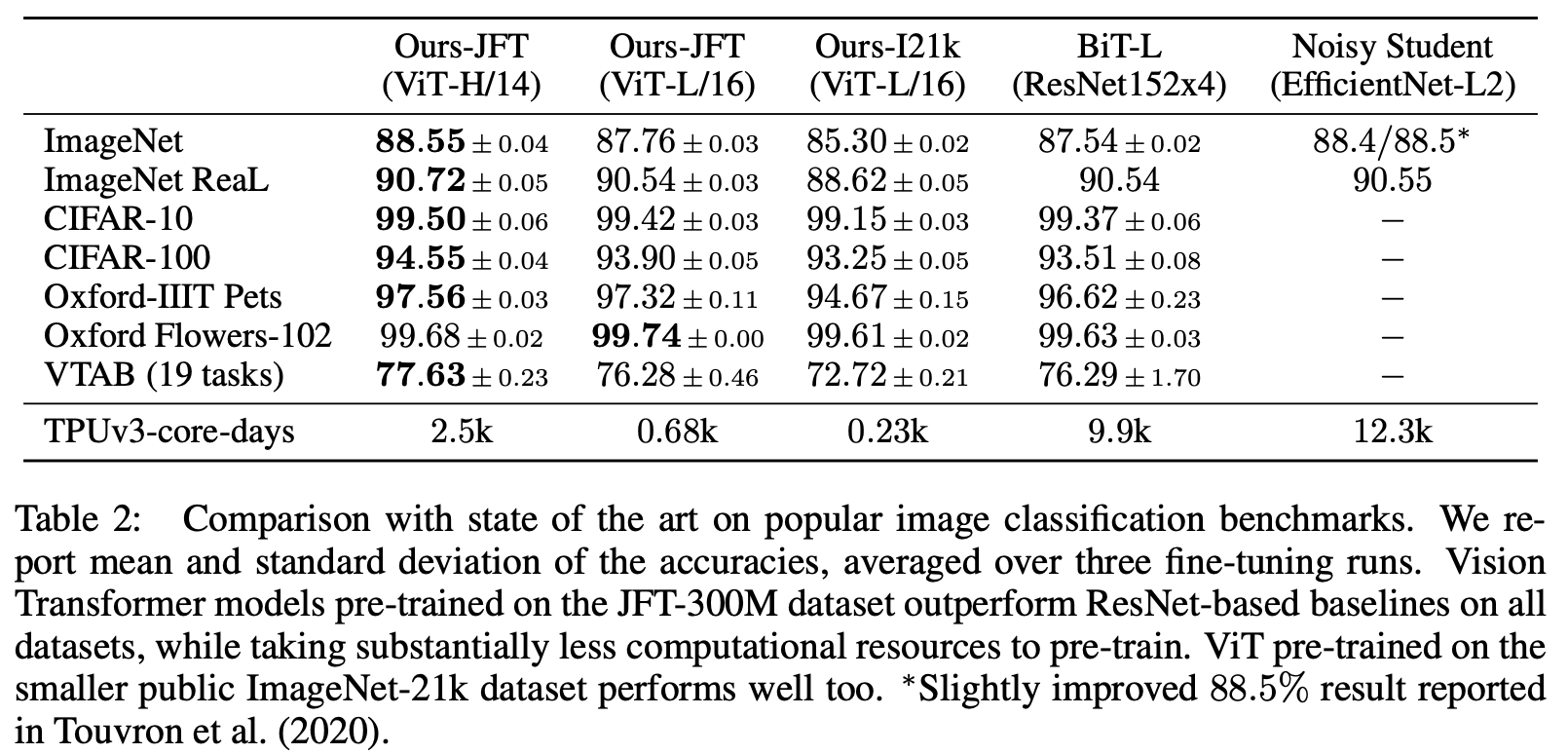

The resulting transformer models are more accurate than the convolutional neural network (CNN) models typically used in computer vision and, more importantly, significantly faster to train. In the table below, from (Dosovitskiy et al., 2020), the first three columns are three versions of the transformer model. The last row shows how the transformer-based networks (first three columns) use substantially less computational resources for training than CNN-based networks (last two columns).

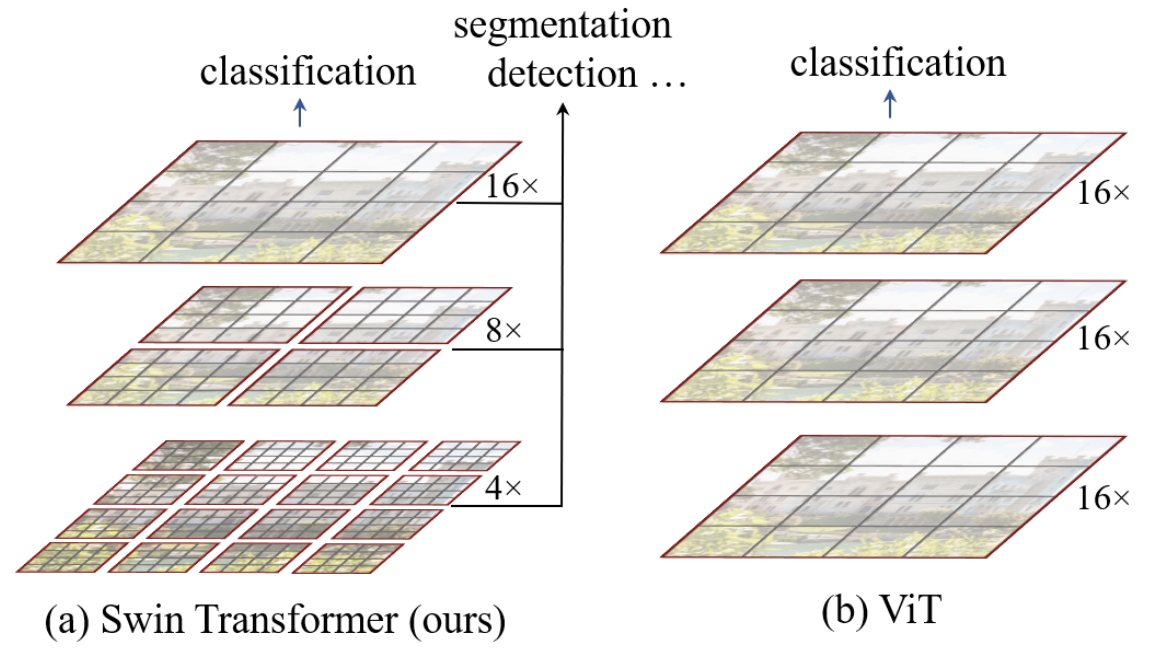

Transformers in computer vision is still an active area of research. At the time of this writing (November of 2021), the recently-published Swin Transformer architecture (Liu et al., 2021) used a shifted windows approach (figure below, from the paper) to achieve state-of-the-art results in image classification, object detection, and image segmentation. The shifted window architecture allows a transformer network to cope with the “…large variations in the scale of visual entities and the high resolution of pixels in images compared to words in text.”

Transformers in healthcare

Applications of Transformers in healthcare fall, in general terms, into the following categories:

- Natural language process (NLP): extract information from medical records to make predictions.

- Genomics and proteomics: processing the large sequences from genetic and proteomic.

- Computer vision: image classification, segmentation, augmentation, and generation.

The following sections describe some of these applications. Note from the dates of the references that this is a recent and active area of research. Many of the current applications of CNNs and RNNs in the same areas have evolved over the years until they reached their current performance. It is expected that these early (and promising) applications of transformers will improve over time as research continues.

NLP applications

The healthcare industry has been accumulating written records for many years. There is a wealth of information stored in these records from consultation notes, lab exam summaries, and radiologists’ reports. Most of them are already stored in electronic health records (EHR), ready to be consumed by computers. Transformers’ success with NLP makes them a good fit to process EHR. Some of the applications include:

- BEHRT (Li et al., 2020), as the name indicates, was inspired by BERT (Devlin et al., 2019). Trained on medical records, BEHRT can predict 301 diseases in a future visit of a patient. It improved the state-of-the-art in this task by “8.0–13.2% (in terms of average precision scores for different tasks)”. In addition to the improvements in prediction, the attention mechanism has the potential to make the model more interpretable, an important feature for healthcare applications.

- (Kodialam et al., 2020) introduces SARD (self-attention with reverse distillation), where the input to the model is not the raw text from medical records but a summary of a medical visit. While BEHRT can handle 301 conditions, SARD can handle “…a much larger set of 37,004 codes, spanning conditions, medications, procedures, and physician specialty.”

Genomics and proteomics applications

Transformers’ ability to process sequences makes them natural candidates for genomics and proteomics applications, where large, complex sequences abound.

- AlphaFold2 (Jumper et al., 2021) is an evolution of the first AlphaFold. It decisively won the 14th Critical Assessment of Structural Prediction (CASP), a competition to predict the structure (“folds”) of proteins. Understanding the structure of proteins is important because the function of a protein is directly related to its structure. Given that the structure of a protein is determined by its amino acid sequence, it is not surprising to learn that one of the most important changes in AlphaFold2 was the addition of attention via transformers (Rubiera, 2021). AlphaFold2’s transformer architecture has been named EvoFormer.

- (Avsec et al., 2021) applied transformers to gene expression. They named the architecture Enformer (“a portmanteau of enhancer and transformer”). Gene expression is a fundamental building block in biology. It is “the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, protein or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype, as the final effect.” (Wikipedia, 2021).

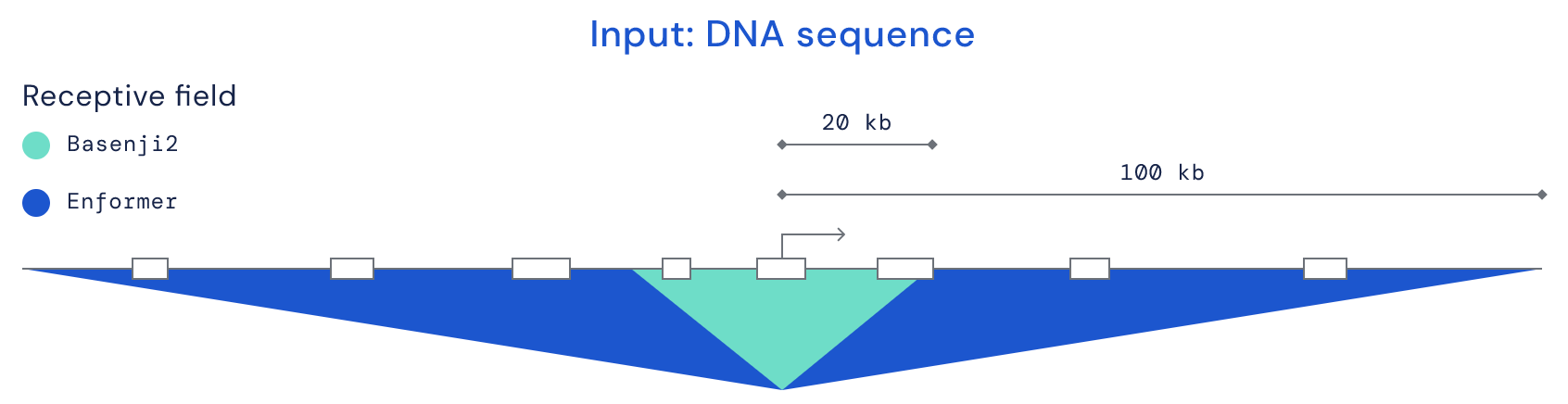

With these applications in mind, the figure below (Avsec, 2021) illustrates why the ability to process larger sequences makes transformers an effective architecture for genomics and proteomics applications. The dark blue area shows how far the Enformer architecture can look for interactions between DNA base pairs (200,000), compared with the previous state-of-the-art Basenji2 architecture (40,000 base pairs).

Computer vision applications

Transformers are improving the following areas of healthcare computer vision:

- Label generation: extract accurate labels from medical records to train image classification networks.

- Large image analysis: process the large images generated in some medical areas.

- Improvements to explainability: produce explanations that are easier to interpret for medical professionals.

The following sections expand on those areas.

Label generation

Medical image applications that identify diseases and other features in images are trained with supervised or semi-supervised learning, which means they need many images with accurate labels. Labeling medical images requires experts that are few, expensive, or both.

On the other hand, there are many images with accompanying medical reports, for example, the radiological reports from x-rays. An application capable of reliably extracting labels from the reports can boost the number of images in medical image datasets. However, medical reports are created by human experts for other human experts. The reports contain complex sentences that record not only the expert’s certainty about findings but also other potential findings and exclusions. Telling apart positive, potential, and negated (excluded) findings is a complex task.

CheXpert (Irvin et al., 2019) made available over 100,000 chest x-ray images with labels extracted from the medical reports using a rule-based NLP parser. The same team later developed ChexBert (Smit et al., 2020) based on (as the name implies) BERT (Devlin et al., 2019). CheXBert performed better than CheXPert and, crucially, it performs better in uncertainty (“potential”, “unremarkable”, and similar words) and negation cases, which are notoriously difficult to analyze.

These results indicate that transformer-based labeling extraction can improve the labels of existing datasets and help create more trustworthy labeled medical images, which are necessary to advance research in healthcare computer vision.

Large image analysis

Some medical diagnosis images, such as those used in histopathology, are large, in the hundreds of megabytes to the gigapixel range. Traditional neural networks cannot handle such images in one piece. Before transformers, a common solution was to split the image into multiple patches and process them separately with a CNN-based network (Komura & Ishikawa, 2018). Dividing an image into arbitrary patches may lose context information about the overall image structure and features.

Holistic Attention Network – HATNet (Mehta et al., 2020) is a transformer-based architecture that takes a different approach, borrowing concepts from NLP. Instead of analyzing each patch separately, it considers each patch a “word” and combines them into bags of words. The bags of words are then processed by a transformer network that aggregates information from the different patches into a global image representation. HATNet is “8% more accurate and about 2× faster than the previous best network”.

More important than the immediate results of HATNet is the innovative approach that opens up the door to more research into processing large medical images. For example, TransUNet (Chen et al., 2021) takes a similar approach for medical image segmentation. As in image classification, CNNs have been traditionally applied to medical image segmentation. Using CNNs for segmentation has a related problem as for classification: the CNNs lose global context. TransUNet resolves that problem with a hybrid architecture: a CNN is used to extract features from the large-dimensional images, which are then passed to a transformer network. It improved the state-of-the-art Synapse multi-organ CT segmentation by several percentage points.

Improvements in interpretability

In high-stakes applications, such as healthcare, interpretable results help improve “auditability, system verification, enhance trust, and user adoption” (Reyes et al., 2020). Specifically for medical images, interpretability is related to explaining what pieces of an image the model considered for inference.

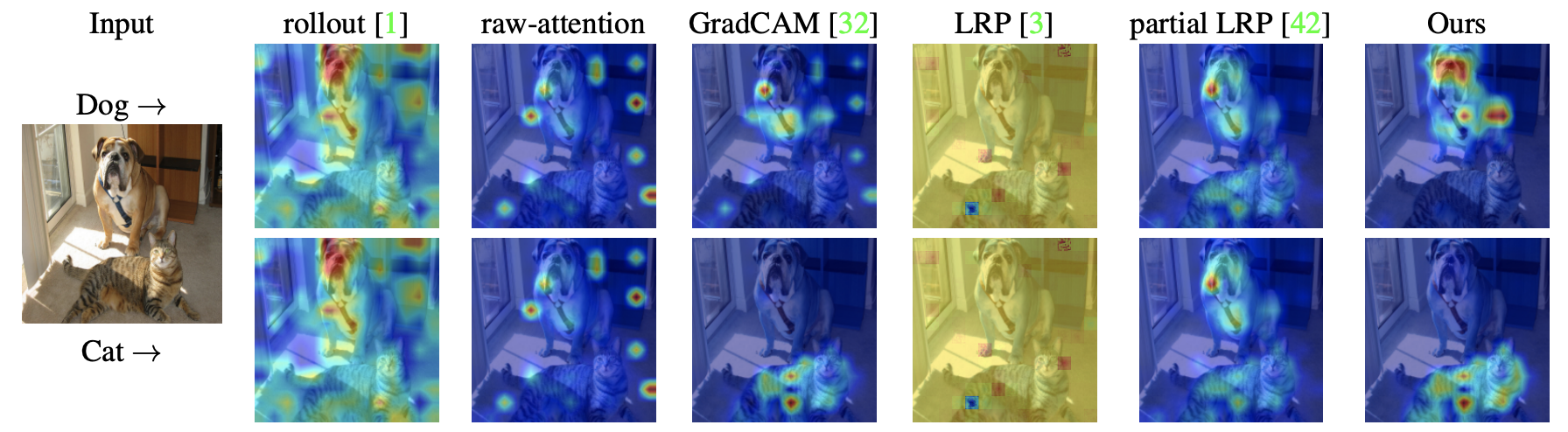

Although still a new field, the interpretability of image classification with transformers shows early signs that it can result in more precise, and thus more helpful, interpretations of what a model is “looking” at. In the figure below, from (Chefer et al., 2021), the rightmost column shows their new method to extract interpretability from a transformer multi-class image classification task. It generates class-specific visualizations with better-defined activations. The closest alternative method is Grad-CAM (Selvaraju et al., 2020) (other methods cannot even generate class-specific visualizations), but it has significantly more extraneous artifacts in the visualization.

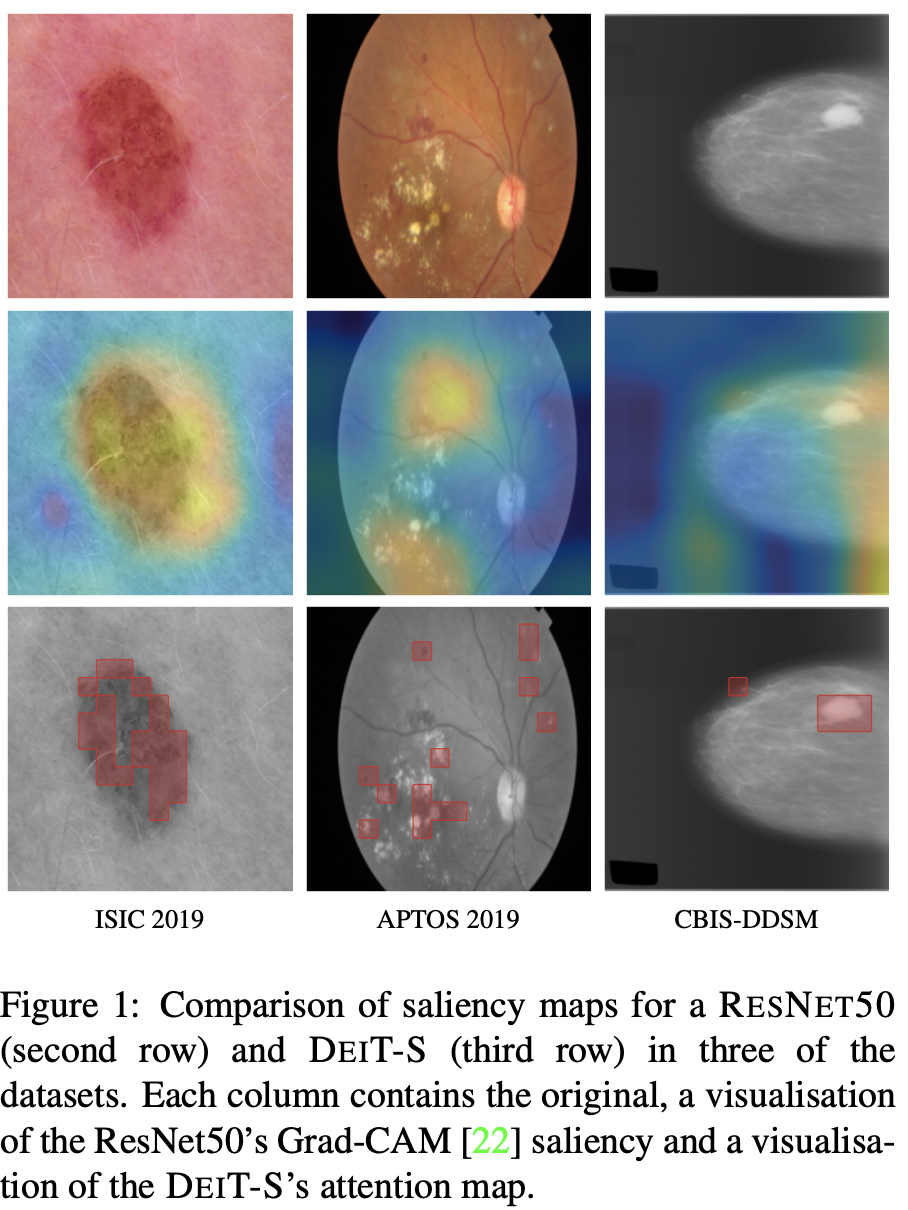

The transformer’s attention map also shows promising results for interpretability. In the figure below, from (Matsoukas et al., 2021), the top row shows the original image of a dermoscopic image (left), an eye fundus (center), and a mammography (right). The middle row is a Grad-CAM saliency map, traditionally used to interpret the classification from CNNs. The bottom row is a saliency map from a transformer attention layer. The attention layer saliency shows a more well-defined saliency area, making the results easier to interpret (although the paper notes that this assumption has to be tested with medical professionals).

Conclusions

Transformers were first used in NLP applications, resulting in impressive language models like BERT, GPT-2, and GTP-3. Their ability to learn the association between pieces of a large sequence of data (attention) is now being used in computer vision. The resulting models are faster to train and more accurate than CNNs for image classification.

From the literature references, we notice that applying transformers to computer vision is still a new area. CNN- and RNN-based solutions evolved over many years of research. We should expect transformers also to evolve. In fact, several approaches are already being tried to create more efficient transformer architectures by, for example, reducing the quadratic complexity of the attention mechanism (May, 2020), (Tay et al., 2020), (Choromanski & Colwell, 2020).

Efficient transformer architectures will have two effects. From one side, larger and larger sequences will be handled, improving the results in applications where the size of the sequence is critical for the results (for example, large resolution images used in healthcare). On the other hand, for the same sequence length, it will become faster, and thus cheaper, to train transformers, democratizing their use.

And, as a final benefit, we may end up with one unified network architecture that can be applied to two important fields, natural language processing, and computer vision.

Appendix A - A reading list for RNN, LSTM, attention, and transformers in NLP

While researching this paper, I started with the original application of the networks, natural language processing (NLP). After researching the applications for image processing, it became clear that starting with NLP was indeed a good choice. The concepts of sequence and attention are easier to illustrate and follow in that area. Once learned in that context, they can be transferred to computer vision.

This appending is a reading list in the context of NLP to help other readers, and the future self of the author when he will (inevitably) have forgotten some of the concepts.

The seminal paper on encoder/decoder combined with RNN for natural language processing is (Cho et al., 2014). (Sutskever et al., 2014) introduced sequence-to-sequence using long short-term memory (LSTM) networks. (Bahdanau et al., 2014) and (Luong et al., 2015) are credited with developing the attention mechanism. (Vaswani et al., 2017) is the original paper on transformers (reading the accompanying Google’s blog post (Jakob, 2017) makes it easier to follow the paper).

The explanations of RNN and LSTM in this paper are simplified because I wanted to focus on transformers. I did not discuss the different types of RNNs and the inner working of the LSTM cell. For a step-by-step, illustrated explanation of how LSTMs work and why it is an effective RNN architecture, see (Olah, 2015). For other RNN architectures, see (Olah & Carter, 2016).

(Alammar, 2018a) describes step-by-step, with the help of animated visualizations the sequence-to-sequence, encoder/decoder, RNN, and attention concepts, including details of how they work. (Alammar, 2018b) builds on that to explain how transformers use the important concept of self-attention, with detailed illustrations.

Finally, as a historical note: finding the original paper on recurrent networks (RNNs) turned out to be elusive. Like many ideas, it evolved over time. (Rumelhart et al., 1987) is credited in several places as the first mention and description of a “recurrent network”, although it did not describe the back-propagation through time (BPTT) method used to train RNNs nowadays.

Appendix B - The quadratic bottleneck

As a general rule, the longer the sequence a transformer can process, the better results it will have. However, it comes at the cost of large amounts of memory and processing power required for training and inference. The self-attention mechanism of the standard transformer architecture is a quadratic function (figure below, from (Tay et al., 2020)).

Several approaches are being tried to reduce the quadratic complexity, creating more efficient transformer architectures (May, 2020), (Tay et al., 2020), (Choromanski & Colwell, 2020).

Efficient transformer architectures will have two effects. From one side, larger and larger sequences will be handled, improving the results in applications where the size of the sequence is critical for the results (for example, large resolution images used in healthcare). On the other hand, for the same sequence length, it will become faster, and thus cheaper, to train transformers, democratizing their use.

References

- Alammar, J. (2018a, May 9) Visualizing A Neural Machine Translation Model (Mechanics of Seq2seq Models With Attention)

- Alammar, J. (2018b, June 27) The Illustrated Transformer

- Avsec, Ž. (2021, October 4) Predicting gene expression with AI. Deepmind

- Avsec, Ž., Agarwal, V., Visentin, D., Ledsam, J. R., Grabska-Barwinska, A., Taylor, K. R., Assael, Y., Jumper, J., Kohli, P., & Kelley, D. R. (2021) Effective gene expression prediction from sequence by integrating long-range interactions. Nature Methods, 18(10), 1196–1203

- Ba, J., Mnih, V., & Kavukcuoglu, K. (2015) Multiple Object Recognition with Visual Attention

- Bahdanau, D., Cho, K., & Bengio, Y. (2014) Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate

- Bengio, Y., Simard, P., & Frasconi, P. (1994) Learning long-term dependencies with gradient descent is difficult. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 5(2), 157–166.

- Brown, T. B., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J., Dhariwal, P., Neelakantan, A., Shyam, P., Sastry, G., Askell, A., Agarwal, S., Herbert-Voss, A., Krueger, G., Henighan, T., Child, R., Ramesh, A., Ziegler, D. M., Wu, J., Winter, C., … Amodei, D. (2020) Language Models are Few-Shot Learners

- Carion, N., Massa, F., Synnaeve, G., Usunier, N., Kirillov, A., & Zagoruyko, S. (2020) End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers

- Chefer, H., Gur, S., & Wolf, L. (2021) Transformer Interpretability Beyond Attention Visualization

- Chen, J., Lu, Y., Yu, Q., Luo, X., Adeli, E., Wang, Y., Lu, L., Yuille, A. L., & Zhou, Y. (2021) TransUNet: Transformers Make Strong Encoders for Medical Image Segmentation

- Cheng, J., Dong, L., & Lapata, M. (2016) Long Short-Term Memory-Networks for Machine Reading

- Cho, K., van Merrienboer, B., Gulcehre, C., Bahdanau, D., Bougares, F., Schwenk, H., & Bengio, Y. (2014) Learning Phrase Representations using RNN Encoder-Decoder for Statistical Machine Translation

- Choromanski, K., & Colwell, L. (2020, October 23) Rethinking Attention with Performers

- Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2019) BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding

- Dosovitskiy, A., Beyer, L., Kolesnikov, A., Weissenborn, D., Zhai, X., Unterthiner, T., Dehghani, M., Minderer, M., Heigold, G., Gelly, S., Uszkoreit, J., & Houlsby, N. (2020) An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale

- Gers, F. A., Schmidhuber, J., & Cummins, F. (1999) Learning to forget: Continual prediction with LSTM. 1999 Ninth International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks ICANN 99. (Conf. Publ. No. 470), 2, 850–855 vol.2

- Greff, K., Srivastava, R. K., Koutník, J., Steunebrink, B. R., & Schmidhuber, J. (2017) LSTM: A Search Space Odyssey. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 28(10), 2222–2232

- Hochreiter, S., & Schmidhuber, J. (1997) Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Computation, 9(8), 1735–1780

- Ian, G., Yoshua, B., & Aaron, C. (2016) Deep Learning

- Jakob, U. (2017) Transformer: A Novel Neural Network Architecture for Language Understanding

- Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A., Green, T., Figurnov, M., Ronneberger, O., Tunyasuvunakool, K., Bates, R., Žídek, A., Potapenko, A., Bridgland, A., Meyer, C., Kohl, S. A. A., Ballard, A. J., Cowie, A., Romera-Paredes, B., Nikolov, S., Jain, R., Adler, J., … Hassabis, D. (2021) Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature, 596(7873), 583–589

- Kodialam, R. S., Boiarsky, R., Lim, J., Dixit, N., Sai, A., & Sontag, D. (2020) Deep Contextual Clinical Prediction with Reverse Distillation

- Komura, D., & Ishikawa, S. (2018) Machine Learning Methods for Histopathological Image Analysis. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, 16, 34–42

- Li, Y., Rao, S., Solares, J. R. A., Hassaine, A., Ramakrishnan, R., Canoy, D., Zhu, Y., Rahimi, K., & Salimi-Khorshidi, G. (2020) BEHRT: Transformer for Electronic Health Records. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 7155

- Lin, Z., Feng, M., Santos, C. N. dos, Yu, M., Xiang, B., Zhou, B., & Bengio, Y. (2017) A Structured Self-attentive Sentence Embedding

- Liu, Z., Lin, Y., Cao, Y., Hu, H., Wei, Y., Zhang, Z., Lin, S., & Guo, B. (2021) Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows

- Luong, M.-T., Pham, H., & Manning, C. D. (2015) Effective Approaches to Attention-based Neural Machine Translation

- Matsoukas, C., Haslum, J. F., Söderberg, M., & Smith, K. (2021) Is it Time to Replace CNNs with Transformers for Medical Images?

- May, M. (2020, March 14) A Survey of Long-Term Context in Transformers. Machine Learning Musings

- Mehta, S., Lu, X., Weaver, D., Elmore, J. G., Hajishirzi, H., & Shapiro, L. (2020) HATNet: An End-to-End Holistic Attention Network for Diagnosis of Breast Biopsy Images

- Mnih, V., Heess, N., Graves, A., & kavukcuoglu, koray. (2014) Recurrent Models of Visual Attention. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 27

- Olah, C. (2015, August 27) Understanding LSTM Networks. Colah’s Blog

- Olah, C., & Carter, S. (2016) Attention and Augmented Recurrent Neural Networks. Distill, 1(9), e1

- Parmar, N., Vaswani, A., Uszkoreit, J., Kaiser, Ł., Shazeer, N., Ku, A., & Tran, D. (2018) Image Transformer

- Pascanu, R., Mikolov, T., & Bengio, Y. (2013) On the difficulty of training Recurrent Neural Networks

- Radford, A., Wu, J., Child, R., Luan, D., Amodei, D., & Sutskever, I. (2019) Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners

- Reyes, M., Meier, R., Pereira, S., Silva, C. A., Dahlweid, F.-M., Tengg-Kobligk, H. von, Summers, R. M., & Wiest, R. (2020) On the Interpretability of Artificial Intelligence in Radiology: Challenges and Opportunities. Radiology: Artificial Intelligence, 2(3), e190043

- Rubiera, C. O. (2021) AlphaFold 2 is here: What’s behind the structure prediction miracle - Oxford Protein Informatics Group. Oxford Protein Informatics Group

- Rumelhart, D. E., Hinton, G., & Williams, R. (1987) Learning Internal Representations by Error Propagation. In Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition: Foundations (pp. 318–362). MIT Press

- Selvaraju, R. R., Cogswell, M., Das, A., Vedantam, R., Parikh, D., & Batra, D. (2020) Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-based Localization. International Journal of Computer Vision, 128(2), 336–359

- Sutskever, I., Vinyals, O., & Le, Q. V. (2014) Sequence to Sequence Learning with Neural Networks

- Tay, Y., Dehghani, M., Bahri, D., & Metzler, D. (2020) Efficient Transformers: A Survey

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, L., & Polosukhin, I. (2017) Attention Is All You Need

- Wikipedia. (2021) Gene expression

- Xu, K., Ba, J., Kiros, R., Cho, K., Courville, A., Salakhutdinov, R., Zemel, R., & Bengio, Y. (2016) Show, Attend and Tell: Neural Image Caption Generation with Visual Attention

- Zaheer, M., Guruganesh, G., Dubey, A., Ainslie, J., Alberti, C., Ontanon, S., Pham, P., Ravula, A., Wang, Q., Yang, L., & Ahmed, A. (2021) Big Bird: Transformers for Longer Sequences